Southern Connecticut State University strives to provide a safe, supportive, and welcoming community for all students to prosper. We stand firmly against any act that could inhibit the growth of others and are united to stand-up against and eliminate hazing. The Violence Prevention, Victim Advocacy, and Support Center (VPAS) provides prevention education on hazing; including an emphasis on ways to be an active bystander and stop it, as well as advocacy and support services for students. We hope to empower students to overcome obstacles and promote growth both inside and outside of the classroom.

What is Hazing?

Definition: Hazing is any activity expected of someone joining or participating in a group that humiliates, degrades, abuses, or endangers them regardless of a person’s willingness to participate.

Three key components of this definition include:

1.) Group context: Associated with the process for joining and maintaining membership in a group

2) Abusive behavior: Activities that are potentially humiliating and degrading, with the potential to cause physical, psychological, and/or emotional harm

3) Regardless of an individual’s willingness to participate: The “choice” to participate may be offset by the peer pressure and coercive/power dynamics that often exist in the context of gaining membership in a group.

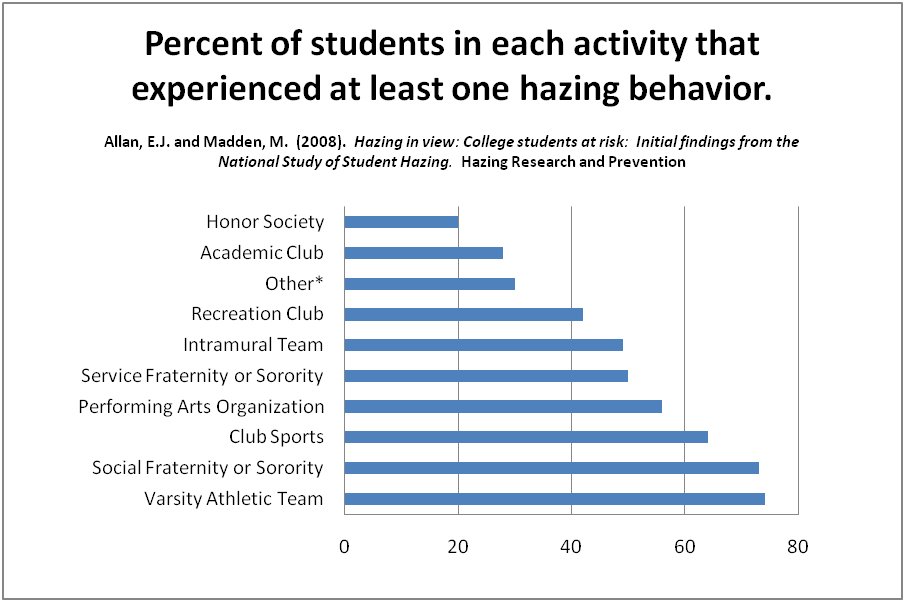

Statistics: 55% of college students involved in clubs, teams, and organizations experience hazing. Hazing occurs in a wide range of organizations, with highest numbers for varsity athletics, fraternities/sororities, club sports, and performing arts clubs.

Types of Hazing

Some behaviors may be harder to define as hazing (e.g. it’s easier to define hazing that includes physical harm, but harder when participants are “willing” or “choose” to participate or when the harm is hidden, psychological, or emotional).

Some examples of hazing include

- Forced and coerced alcohol consumption

- Drinking games

- Requiring members to wear pledge pins

- Paddling

- Required to humiliating or degrading behavior

- Sexualized and sexual harassment hazing

- Sleep deprivation

- Yelling and screaming at team/organization members

- Being transported to and dropped off at unfamiliar location

- Beating, zip ties

- Reckless driving

- Sexual Assault

- Servitude

- Isolation

- Sex acts

- Public humiliation (like wearing embarrassing clothing)

- Required to take organizational tests or perform specific menial tasks in order to continue involvement with the group

Impact of Hazing

The degree of potential harm from hazing may be measured relative to particular behavior. Some students have lost their lives as a result of hazing. Some student hazing victims want to leave campus or choose to transfer institutions. Many hazing victims feel confused, upset, or isolated but don’t feel comfortable speaking out. They also talk about wishing they had support in changing some of the behaviors they were seeing on their campus. Some students who experience or observe hazing feel guilty, even when the hazing isn’t their fault.

Other negative effects of hazing include:

- Relationship problems (like difficulty trusting others)

- Trouble sleeping

- Impaired concentration

- Loss of academic progress

- Feelings of humiliation or depression

Barriers to Speaking Out

Some barriers reported by hazing scholars include:

- Not wanting to get their team or group in trouble

- Fear of retaliation and/or negative consequences from other team or group members

- Fear that others would find out about the report and they’d be excluded

- Not knowing how or where to report

- Not recognizing an experience as hazing, rationalize or normalize the experience (as “tradition,” as part of group bonding, etc.)

- Thinking that they shouldn’t report because they chose to participate in the hazing activity

- Conclude that an incident was not notable enough to report

What Can You Do?

In a 2008 study, 69% of students who belonged to a student group reported that they were aware of hazing activities occurring in student organizations other than their own. This means that oftentimes students may know hazing is occurring within an organization, but are unsure of what they can do to change it.

Learn More

Learning about what members feel about hazing is critical to acquiring accurate perceptions of peers’ actual beliefs and values related to hazing. Research suggests that students often misperceive the extent to which their peers are comfortable engaging in high risk behaviors like hazing and that if they thought that a majority of their peers were uncomfortable with hazing, they would be more likely to decline to participate

Here are a few other ways students can make a difference:

- Leaders within organizations could choose not to implement hazing practices.

- Engage the group in an alternate activity to create group unity.

- Anticipate that hazing may occur, talk with other members of the group who do not support hazing, and plan ways in which you can work together to intervene if it does occur.

- Reach out to individual members to see how they feel about specific activities.

Talk About It

Many hazing activities are planned in advance. Having conversations with members and friends about definitions of hazing and types of hazing behaviors may help others to “think twice” about what’s happening. Talking about hazing can broaden awareness of hazing, help others to notice it, and also contribute to making it less covert.

- Listen carefully to stories shared by friends and be available to talk with them about how they feel about their own experiences relative to hazing and other behaviors. Students are most likely to tell friends or family about hazing experiences.

- Report hazing behavior to a trusted adult and/or campus official.

- Call 911

Bystander Intervention

There are a few critical steps bystanders can take to address hazing on campus.

- Discuss what each of these items might entail in action:

- Notice hazing

- Interpret hazing as a problem

- Recognize a responsibility to change it

- Acquire the skills needed to take action

- Take action (safely)!

Team-Building Activities

Create new and positive traditions with your team or organization that encourage, empower and bond each other. Some ideas include:

- Community service activities or trips

- Attending a movie or concert together

- Mentoring (i.e. program in which students from the same major are paired together)

- Group outings or activities (i.e. bowling)

- Ropes courses and problem solving games] with trained professional guidance and supervision

Request a Program

- Hoot against Hazing

- Contact us for hazing presentation that will define hazing and increase recognition, discuss healthy team building activities and bystander intervention and will provide information on reporting, advocacy and support services.

SCSU Reporting, Advocacy and Support Options

Hazing is not acceptable at SCSU. It is a violation of the Student Code of Conduct and against Connecticut State Law;

Reporting Options

- University Police: (203) 392-5375 or 911

- Local Police: 911

- Dean of Students Office: (203) 392-5556

- Office of Student Conduct and Civic Responsibility: (203) 392-6188

Advocacy and Support Services

- Violence Prevention, Victim Advocacy and Support Center: (203) 392-6946

- Counseling Services: (203) 392-5475

- Interfaith Office: (203) 392-533: Adanti Student Center 227

Resources

- CleryCenter.org

- StopHazing.org

- HazingPrevention.org

- The National Collaborative for Hazing Research and Prevention

Information retrieved from CleryCenter.org.